I

mentioned back at Ash Wednesday that one of my Lenten reads was Compassionate Blood, a meditation on the

Christ's Passion from the words of the patron saint of this blog, St. Catherine

of Siena. I wanted to go through one of

the chapters to give you a feel for the book, but also to once again to show

the sparkling thoughts of this wonderful little lady on her feast day, April 29th. This comes from the book’s chapter titled

“The Cross.” Cessario here takes

Catherine’s exegesis on a well-known verse from Paul’s epistle to the Romans, “I

consider that the sufferings of this present time are as nothing compared with the

glory to be revealed for us” (Rom 8:18).

Catherine once wrote to a

certain woman, Nella Buonoconti, a wife and mother who lived with her family in

Pisa and whose son had extended hospitality to Catherine and her “family”

during their stay in that northern Italian city. Here is what she said: “The sufferings of this

life are not worth comparing with the future glory that God has prepared for

those who reverenced him and who with good patience endured the holy discipline

imposed on them by divine Goodness. In

their patience, these people are experiencing even in this life the earnest of

eternal life” (Letters II, 459). Her words introduce an especially comforting

word that Jesus spoke from the cross: “Then [the good thief] said, ‘Jesus,

remember me when you come into the kingdom.’

He replied to him, ‘Amen, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise’”

(Lk 23:42-43)…What, however, explains that only one of the two criminals who

were crucified with Jesus received this remarkable grace to turn to him and

seek an “earnest of eternal life”?

The answer to that

question lies in why the good thief, traditionally known as Dismas, makes his plea

to Christ.

To discover how an

everyday thief became a good thief, we must consider two themes: first, the

immensity of divine grace and, second, the efficacy of Christ’s death on the

cross…These themes dominate the spiritual doctrine of St. Catherine of Siena…

Those two themes reach to

the heart of Christianity. If you have

to remember two elements of Christianity, remember divine grace and the

transformation of the world by Christ’s crucifixion.

To another woman, one

moreover who enjoyed a reputation for indulging worldly desires, Catherine felt

compelled to explain the dynamics of divine law. “But you will say to me,” she wrote to Regina

della Scala, “’Since I have no such love, and without it I am powerless, how

can I get it?’ I will tell you,” Catherine continues. Her reply seems too simple for the

theologically sophisticated to take seriously, but Catherine’s authority trumps

such a phony demurral. “Love,” explains

Catherine, “is had only by loving. If

you want to love, you must begin by loving.” (Letters I, 73)

Love is integrally

connected to grace.

God never abandons

us. The divine goodness remains present

to us, always there to fill up what is empty and vacant in our lives. This assurance explains why Catherine

instructs Regina della Scala that she should become accustomed to reflecting on

her own nothingness. “And once you see

that of yourself you do not even exist,” Catherine explains, “you will

recognize and appreciate that God is the source of your existence and of every

favor above and beyond that existence—God’s graces and gifts both temporal and

spiritual.” (Letters I, 73) Instead of emphasizing the disjunctive

conjunctive either/or, Catherine prefers what Hans Urs von Balthasar later

called “the catholic and.” (The

Office of Peter and the Structure of the Church, Ignatius Press, 1974, pp.

301-7) Divine premonition and human freedom. Divine grace and human nature. God and

the cross of God’s only son. “For

without existence, we would not be able to receive any grace at all,” Catherine

writes to Regina. “So everything we

have, everything we discover within ourselves, is indeed is indeed the gift of

God’s boundless goodness and charity.

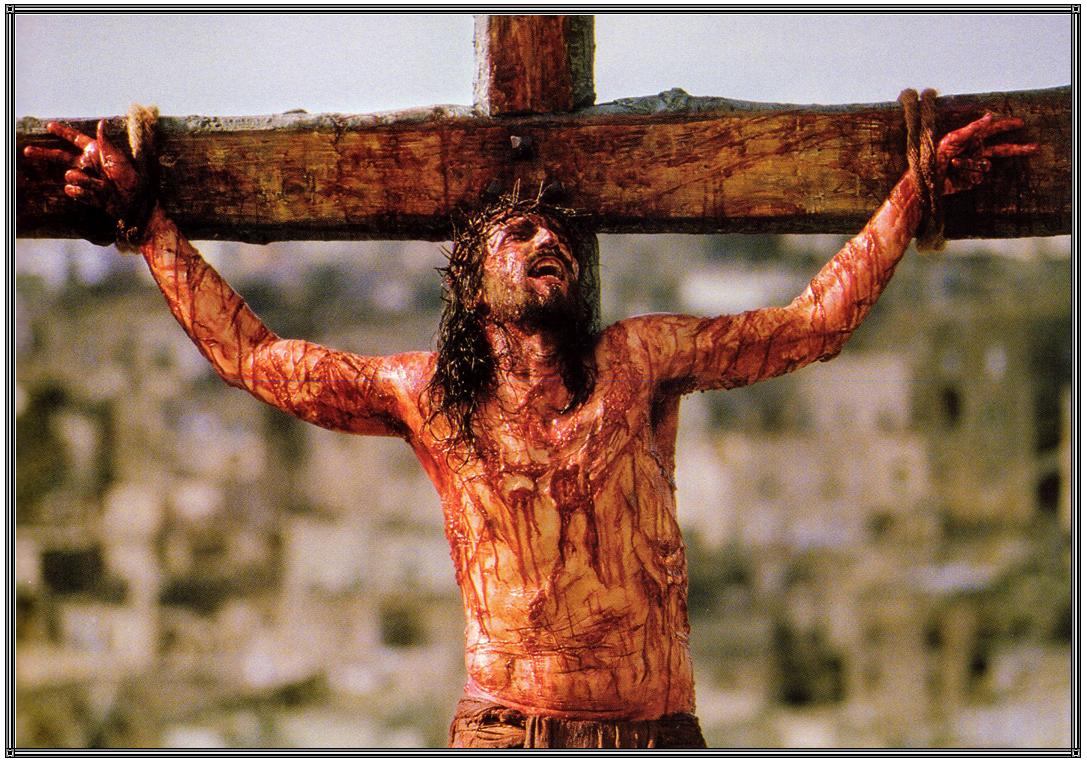

And the crucifixion is

actually God’s greatest grace, his deepest expression of love. Love and grace meet—buckle—at the cross.

“When we see ourselves

loved we love in return,” she assures us.

(Letters I, 73) On the cross, Christ exhibits the greatest

possible love, so says Saint Thomas Aquinas.

(Summa Theologiae IIIa q. 48,

a.2) Catherine calls the cross “love’s

fire”; fed in this fire, “we realize how loved we are when we see that we

ourselves were the soil and the rock that held the standard of the most holy

cross.” (Letters I, 73) In other words, in order to appreciate the

place we poor sinners hold in the drama of Christ’s Passion, we need first to

find comfort from “love’s fire,” from the holy cross of sweet Jesus crucified. Like a little moth that can only find itself

drawn to the fire that will consume it, the soul finds itself drawn to the

cross. And what do we find when we land

close to “love’s fire”? “That neither

earth nor rock could have held the cross, nor could the cross or nails have

held God’s only-begotten Son, had not love held him fast.” (Letters

I, 73) Catherine’s catechesis

reaches its completion. What moved the

good thief? Love. God’s love.

God’s love shining through the human face of the Savior.

Not bad from an

uneducated woman from the Middle Ages. Compassionate Blood is a nice little

devotional.

St. Catherine of Siena,

on your feast day, pray for us.